We often hear that about 80,000 people commute into Ann Arbor for work. How do we know that? Where does that kind of number come from?

One source is the Census Bureau's OnTheMap site.

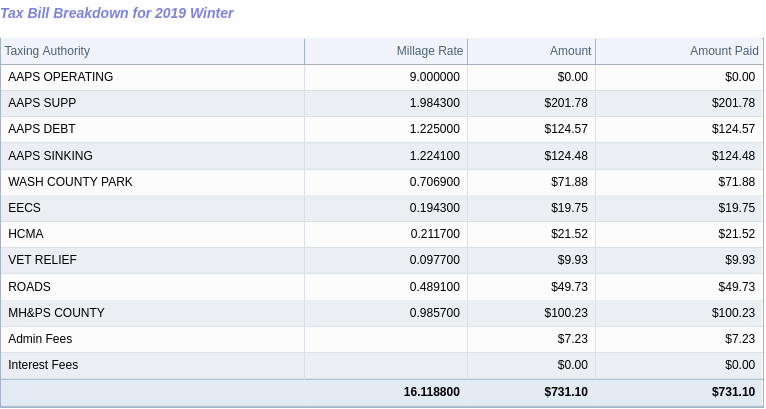

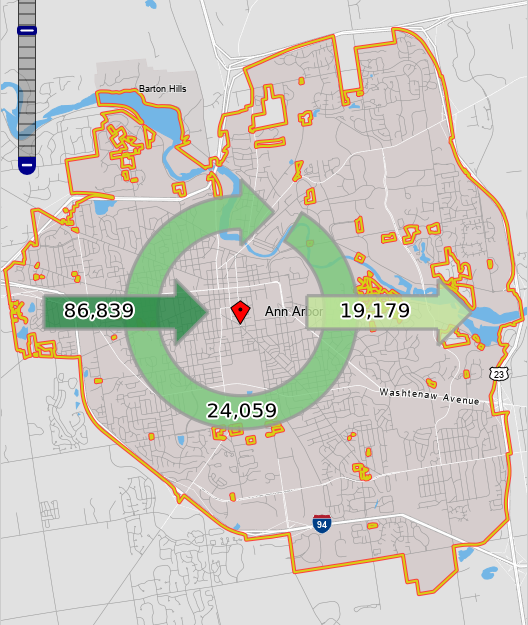

You can look up numbers there; to get the following chart, I searched for Ann Arbor city, chose "Perform Analysis on Selection Area", then "Inflow/Outflow" and "Primary Jobs" from the following dialog. This shows that about 86,000 work in Ann Arbor and live outside, 24,000 both live and work in Ann Arbor, and 19,000 live in Ann Arbor and work elsewhere:

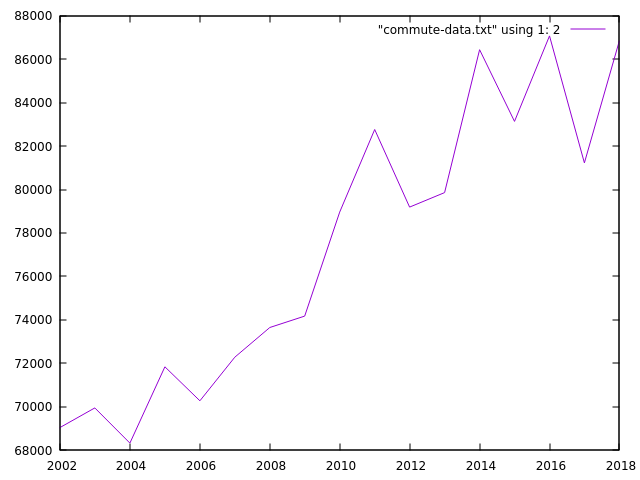

You can also ask for multiple years:

The data is assembled from a number of sources; see the documentation at the OnTheMap site for details.

Semcog's Commuting Patterns site is another convenient source. They report that 72,552 people worked in Ann Arbor and lived elsewhere in 2016, and report 63,420 for 2010. So, their numbers are in the same ballpark as the OnTheMap numbers, and show the same trend, but it would be interesting to understand why they're different. The estimate of number of people working in Ann Arbor is very close (comparing the 2016 numbers--111,290 for OnTheMap, 112,878 for semcog), but their estimate of number of people both living and working in Ann Arbor is very different (24,230 for OnTheMap, 40,326 for SemCog).

Semcog's source appears to be CTTP, specifically I think it's mainly question 31 from the American Community Survey (ACS): "At what location did this person work LAST WEEK? If this person worked at more than one location, print where he or she worked most last week."

OnTheMap/LODES appears to be based mainly on unemployment insurance and (for federal employees), the Office of Personnel Management. Anecdotally, there's some skepticism about whether they get employer locations correct, and I also wonder whether they might be counting as in-commuters some students who list their parents' addresses on employment records but actually live in town. The LODES data may still be useful at least for comparisons across time, though.

We also have forty-thousand-some students who need to get between home and campus daily. Jonathan Levine points out SCIP, which has some useful data. They report 95% of student residences as in the "Ann Arbor area". Unfortunately they define "Ann Arbor area" using zip codes that extend out into the townships, so it's not directly comparable to the above data. They also have some interesting-looking information about commute modes and employees.

Of course, all this is based on data about where people live and where they work. It would also be interesting to compare with data about traffic; this county road commission site looks like one good starting point.

Other stuff to follow up on:

- A Survey of Downtown Ann Arbor Commuters and Decision-Makers (2018).

- https://htaindex.cnt.org/ makes it easy to compare statistics like vehicle miles traveled for Ann Arbor and surrounding areas.

- This article looks like a good introduction to some of these sources.

- Mobility in Ann Arbor: Today Factbook from 2019.